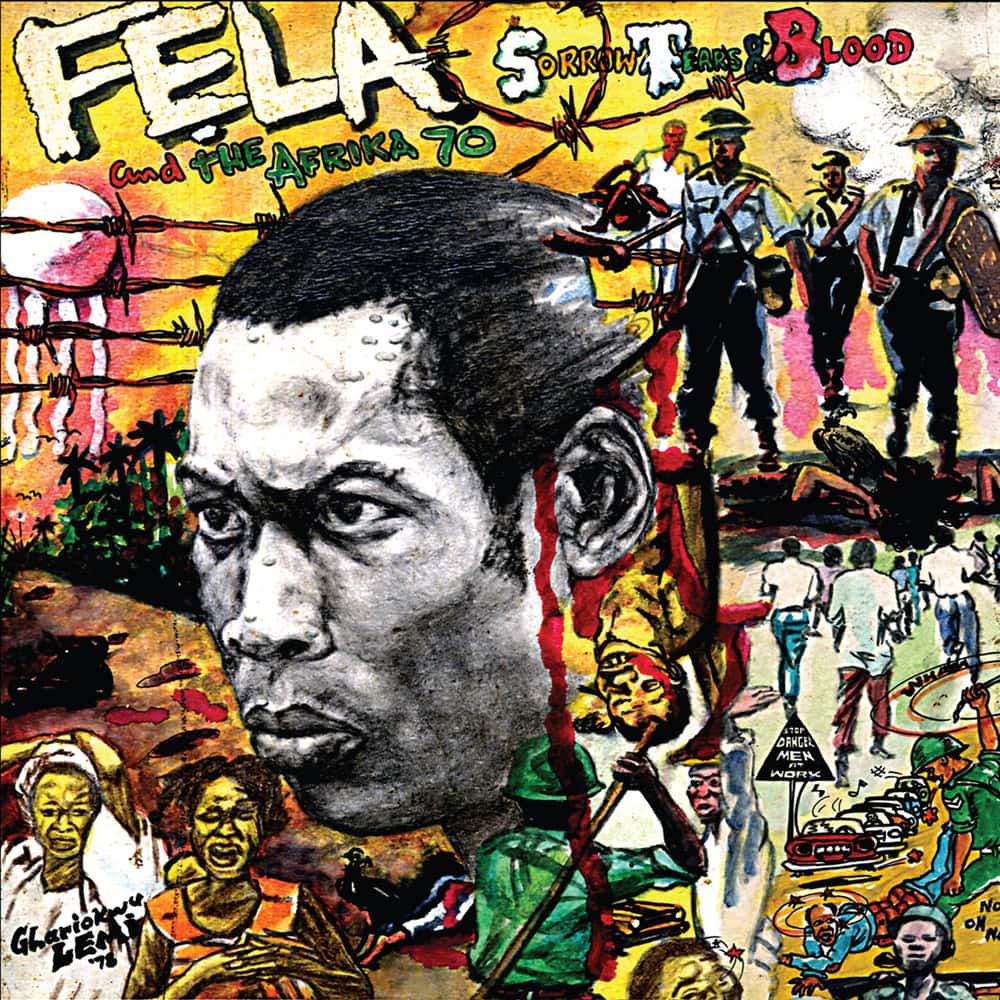

“Sorrow, tears and blood, them regular trademark”

Fela’s song is a perfect illustration of the police brutality still occurring today in Cameroon (and elsewhere). I grew up under the totalitarian regime of Ahmadou Ahidjo and was subject to regular roundups in New-Bell Bonadibong, a popular pan-African district of Douala, the country’s economic capital. This song is by no means a coincidence: the military’s fierce revenge had just fallen on Kalakuta Republic, Fela’s stronghold. And all of a sudden, at three o’clock in the morning under the pouring rain, a whole mixed battalion came down on us all. An “elite” corps made up of police officers, soldiers and other armed officers. Masters of their rifles’ triggers and grips… In short, masters of everything that could be used for exploding rebellious skulls. In this context, the title “Sorrow Tears and Blood” makes sense.

The siren screams!

Eh-ya!

Everybody run run run

Eh-ya!

Everybody scatter scatter

Eh-ya!

Some people lost some bread

Eh-ya!

Someone nearly die

Eh-ya!

Someone just die

Eh-ya!

Police they come, army they come

Eh-ya!

Confusion everywhere

Eh-ya!

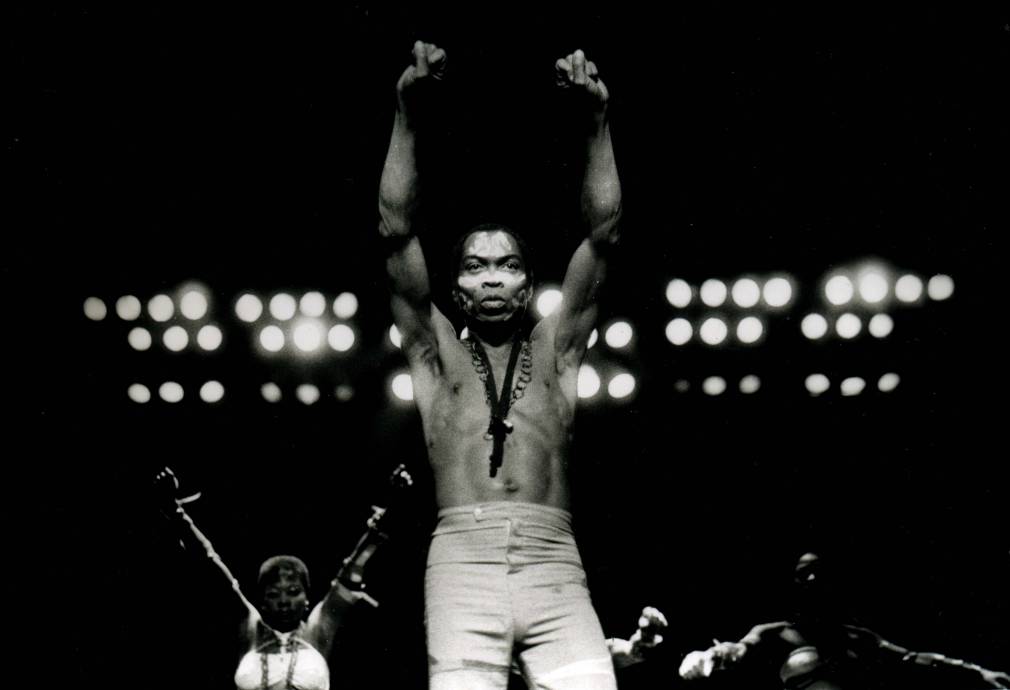

In order to fully appreciate the weight of these words, let’s go back to the beginning of the story, in 1976 when Fela’s song “Zombie”, a scathing antimilitarist satire, was released. This track mocks the Nigerian army and its decerebrated robot-soldiers, as a bunch of zombies: “Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go / Zombie no go stop, unless you tell am to stop / Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think (Zombie) […] Go and kill! / Go and die! […] Quick march! / Slow march! / Left turn! / Right turn!” Fela chanted, enraged yet with a sense of irony.

The military junta did not forgive Fela’s insolence and his determination to denounce the military and police brutality, the abuse of power, the endemic corruption, bad governance and its associated dysfunctions established as the unique modus operandi… Not to mention Fela’s boycotting of FESTAC ’77 (World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture), the second edition of the World Festival of Black Arts, organized by the government in Lagos.

Fela would even have the impudence to launch his own own counter-festival. After the official shows of Stevie Wonder, James Brown and other great performers, the artists themselves as well as international journalists would rush to the Africa Shrine to attend Fela’s performances and visit his own Kalakuta Republik. This was the height of humiliation for the junta in power. Olusegun Obasanjo, the president of Nigeria at the time, then took advantage of an altercation between the police and a member of Africa ’70, Fela’s orchestra. The police wanted to arrest him and appeared in front of Kalakuta where he had taken refuge. But with no warrant to produce to Fela, he refused them to enter his territory. General Obansajo therefore sent the army and police against the Kalakuta Republik. And then things got out of control!

When the zombies showed up in Kalakuta

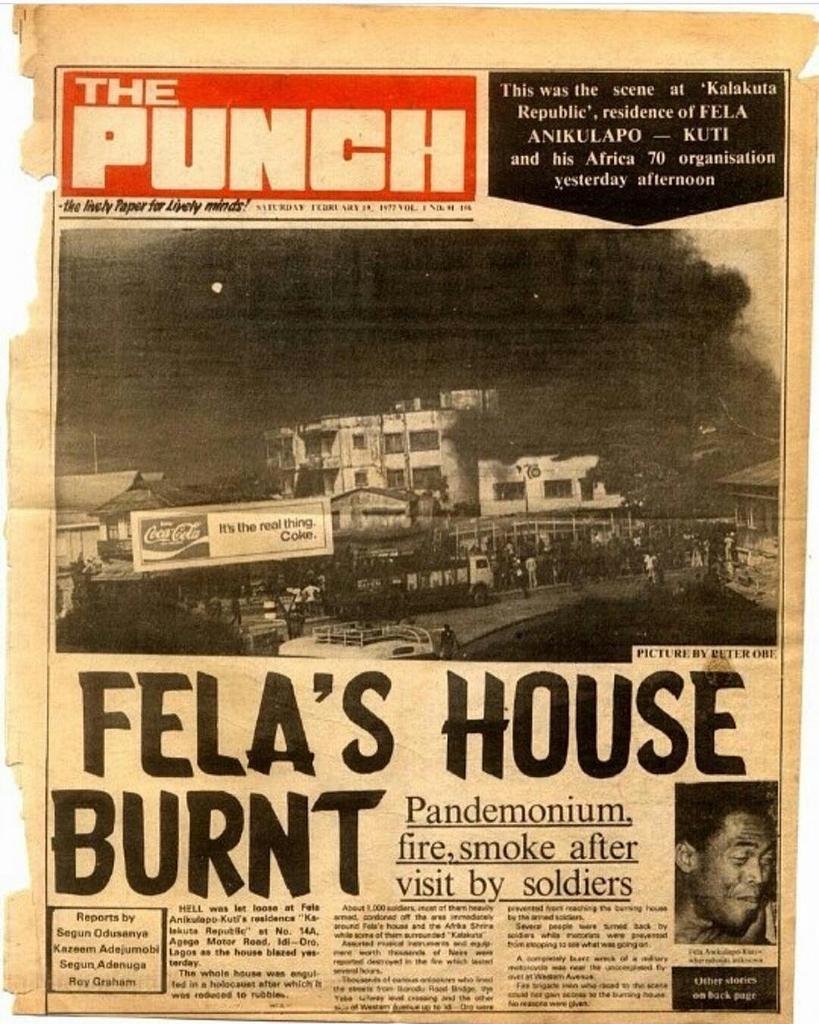

On February 18, 1977, the house of Fela Anikulapo Kuti got burnt by the army. The artist’s utopia of a land of asylum open to all the outcasts left in Lagos went up in smoke. That same gruesome day, Funmilayo Kuti, Fela’s mother, was thrown out of a window. A major figure for Panafricanism, an activist for the anti-colonial struggle with Kwame Nkrumah, died shortly afterwards from her wounds.

The event directly inspired “Sorrow Tears and Blood”.

Eh-ya!

Everybody run run run

Eh-ya!

Everybody scatter scatter

Eh-ya!

Some people lost some bread

Eh-ya!

Someone nearly die

Eh-ya!

Someone just die

Eh-ya!

Police they come, army they come

Eh-ya!

Confusion everywhere

Eh-ya!

Seven minutes later

All don cool down, brother

Police don go away

Army don disappear

Them leave sorrow, tears and blood

Them regular trademark

Them leave sorrow, tears and blood

Them regular trademark

As was Fela’s habit through his songs, the singer chronicled Lagos, Nigeria and Africa. The song “Sorrow Tears and Blood” was released that same

Since New-Bell Bonadibong, the injustice Fela had to cope with strongly resounds in me. I’m 23, and I’ve immersed myself in the world of Fela since I was 17 years old. He is the landmark of my adolescence, and our torchbearer. He enlightens us, educates us, opens our eyes to ourselves. He makes us proud to be African, and encourages us to be indignant. He is one of the very few African musicians to refuse to compromise with Africa’s gravediggers and corrupt politicians. Through his music and revolutionary stances and attitude, he opened the realm of possibility: the dream of another Africa that stands up. But he also knew how much the tyrants of the continent control through fear and terror, as he reminded us:

My people self they fear too much

We fear for the thing we no see

We fear for the air around us

We fear to fight for freedom

We fear to fight for liberty

We fear to fight for justice

We fear to fight for happiness

We always get reason to fear:

We no wan dieWe no wan wound

We no wan quench

We no wan goI get one child

Mama dey for house

Papa dey for houseI wan build house

I don build house

I no want quench

I want enjoy

I no wan go

Ah!

So policeman go slap your face

You no go talk

Army man go whip your yansh

You go they look like donkey

Rhodesia they do them own

Our leaders they yab for nothing

South Africa they do them own

Them leave sorrow, tears and blood

Them regular trademark

It should be noted that in Cameroon we share the Pidgin language in common with Nigeria, and therefore we have the privilege to understand Fela’s lyrics that elude some of our brothers in the French-speaking regions. They rarely have a thorough access to the accuracy of his words and even less to the relevance of his analysis. Many have only an image complacently distorted by part of the media. There is no doubt Fela frightened – and still does – most of Africa’s governing politicians. They fear the influence he could have on young people in their respective countries. The destruction of the “republic of the outcasts of Lagos” is therefore a blessing for some of them, but a real disaster for the rest of us.

Epilogue: return from Nigeria, to bring back the good word of Fela, at the risk of my own life

Meanwhile, I decide to make a pilgrimage to the ruins of Kalakuta and bring back to Cameroon a pile of LPs of Sorrow Tears and Blood. I obviously do not have a passport, and therefore no other choice but to leave Cameroon in clandestine, using a narrow canoe until Oron, a small port in southeastern Nigeria, another clandestine destination. The journey goes without a hitch, until Lagos.

But on my way back, the travel from Oron is acrobatic. All the undocumented migrants have greased the smugglers’ palms, who in turn have bribed the border police. We ship. Engine on! Let’s go!

There we are: forty “illegal” migrants perched on a mountain of various goods. An indescribable pile of bric-a-brac. The ocean suddenly rages. Huge waves rush into our precarious wooden craft. The boat is pitching. The starboard side rocks. The smugglers shout, “owona balance canoe!” Balance the canoe! Everyone crawls to port to straighten the bar. A wave as huge as a mountain eventually sweeps our efforts. “Owona balance canoe ooo!” Everyone to starboard! Tidal wave inside the hull. Imminent sinking. Panic is gaining ground on board…

Then an engine breaks down. No more light. A jet-black night envelops us. We have totally given over to the raging elements. And up there, not a single star to guide us. We are lost. The ocean roars. Thunder rumbles. A lightning bolt rips the sky. Successions of waves submerge the hull.

You can hear a few “Ave Maria!” and “In the name of Jesus!” among other “Allahu Akbar!”, spontaneous interjections that fear produces. Any “infidel” immediately turn themselves into fervent believers.

The makeshift craft is about to sink. I’m not that keen to end up in the belly of a shark. We must do something other than pray, for goodness sake! I place my box of Fela’s records behind me to protect them, and I start to throw other people’s baggage into the sea so that it lightens the canoe. Who is the crazy one? Some protesting begins, but I do not care. Another passenger follows on my heels and starts to scoop the water off the canoe. The boat lightens and starts to regain its surface. It is then that a miracle occurs. A monumental wave carries the canoe and throws it onto Limbé’s beach. I desperately cling to my record box. Victory! I am in Cameroon with the latest Fela album! Sorrow Tears and Blood arrived safely, and so did I. Not without fear, not without tears.